Exeter College holds portrait conservation summer school

From top left to right: Jack Chauncy, Alexandra Earl, Georgie Dennis (organiser and freelance conservator), Paul Kisner, Rebekka Katajisto, Elisabeth Subal, India Ferguson, Kyoko Takemura, Momoko Okuyama, Jessie Carter, Megan Buchanan-Smith, Marie-Christine Livage (organiser), and Sophia Boosalis.

During two sunny August weeks, a cohort of painting conservation students from The Courtauld Institute of Art in London, The Hamilton Kerr Institute in Cambridge, and the Stichting Restauratie Atelier Limburg (SRAL) in the Netherlands attended the Exeter College Conservation Summer School. Organised by professional conservator Georgina Dennis (1988, Modern History), the Summer School attendees treated seven paintings and their frames from the College hall. The portraits date from the seventeenth to twentieth century.

The conservation work was completed in a marquee on the College’s front quad. / © Marie-Christine Livage

Following several decades of hanging on the College hall walls, the paintings had accumulated significant layers of dust and debris trapped behind their stretchers. Each portrait required different treatments depending on their condition and composition, as well as what could be realistically achieved within the two-week time frame.

Liz Herbet, Megan Buchanan-Smith and Sophia Boosalis conducting a condition check and dry surface cleaning of the Portrait of Thomas Secker / © Marie-Christine Livage

Rebekka Katajisto and Kyoko Takemura removing varnish from the Portrait of Sir John Acland / © Marie- Christine Livage

After allocating paintings to groups, the necessary documentation was completed for every portrait. Each artwork’s condition was checked, a treatment proposal was devised, and photographs were taken before any work could begin. The goal of each treatment was to improve the aesthetic and structural integrity of the painting and its frame, whilst being consistent with the other works at Exeter College.

Portrait of Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury

Paul Kisner, Kyoko Takemura, and Rebekka Katajisto cleaning the frame of the Portrait of Anthony Ashley Cooper / © Marie-Christine Livage

Dry methods were used to remove the dust and loose particulate dirt from the majority of the paintings and frames, including the Portrait of Thomas Secker and the Portrait of Anthony Ashley Cooper. Students cleaned the verso of the canvases primarily with cardboard slides, a soft Japanese brush, and a low-suction vacuum to reach the dust trapped behind the stretcher bars. Segments of smoke sponge were gently massaged across the back of the canvases in order to remove the dirt that had become encrusted in the weave.

Portrait of Edwin Lankester by John Collier, 1904

Momoko Okuyama, Jessie Carter, India Ferguson, and Rebekka Katajisto surface cleaning the Portrait of Edwin Lankester / © Marie-Christine Livage

The Portrait of Edwin Lankester was first surface cleaned using triammonium citrate (TAC) solution which was applied with cotton swabs and rinsed with deionised water. The yellowed varnish was removed using a 9:1 ethanol to iso-octane mixture. This was originally applied using minimally saturated sheets of Evolon tissue applied to the surface in 7x7cm squares for 60 seconds. Overall, this method successfully removed the discoloured varnish which had previously concealed the crustaceans in the foreground. These pictorial elements are integral to the portrait as they illustrate Lankester’s career as a zoologist and biologist, and his pioneering research in evolution and invertebrates at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Liz Herbet consolidating and repainting the frame for the Portrait of Edwin Lankester / © Marie-Christine Livage

The painting’s gilded frame had areas of flaking, which were consolidated with glue and locally weighted. Ingrained surface dirt and the discoloured coating were removed using deionised water applied with makeup sponges and cotton swabs. Furthermore, the losses were filled and remodelled with gesso which were subsequently retouched with watercolour and gold paint.

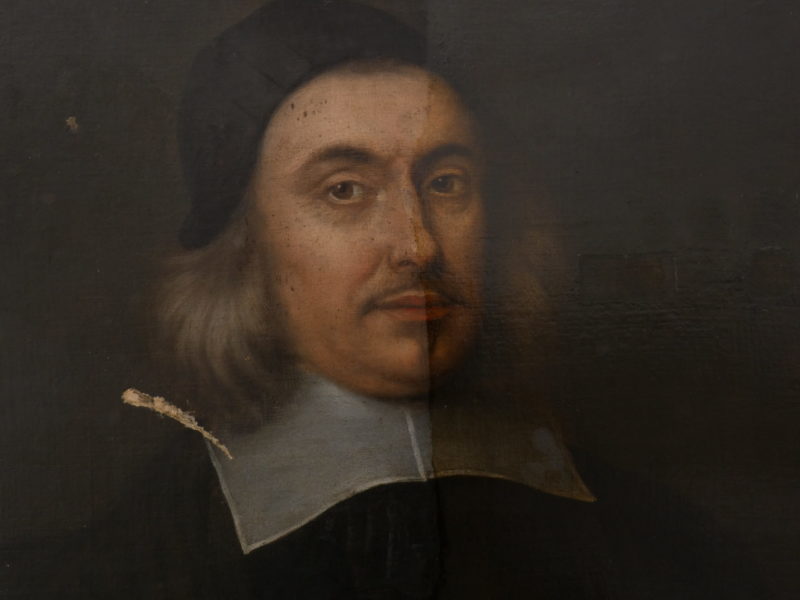

Portrait of John Conant, 1660

A visible light and ultraviolet light photograph of The Portrait of John Conant showing the varnish removal process / © Marie-Christine Livage

The Portrait of John Conant had not been removed from the dining hall wall for approximately 200 years. As a result, the painting exhibited a thick layer of dirt and debris on the frame and behind the stretcher. Following a surface clean of the painting’s verso and recto, varnish removal tests were conducted to ensure safe removal of the varnish from the painting. Having visually identified a natural resin varnish, Evolon tissue with Klucel gel was used to remove the thick varnish and layers of black soot.

Elisabeth Subal applying an isolating varnish layer / © Marie-Christine Livage

Old fills were removed and reduced by scraping them with a scalpel to the same level as the paint surface. During this process, it was observed that most fills covered original paint without there being a loss or damage that required filling. Tenting paint flakes (in areas of the black clothing and background) were also consolidated with isinglass, which was fed into the cracks with a paintbrush and then adhered with a hot spatula.

Elisabeth Subal applying an isolating varnish layer / © Marie-Christine Livage

An isolating varnish was applied to the painting with a brush so filling and retouching could commence thereafter.

Alexandra Earl and Jack Chauncy retouching paint losses / © Marie-Christine Livage

Filling was undertaken using chalk and glue. Retouching was carried out using dry pigments and B72 in Shellsol A for the base colours, followed by Laropal A81 in Shellsol D and A with Gamblin Colours.

Alexandra Earl and Jack Chauncy with the restored portrait / © Marie-Christine Livage

The painting’s frame was cleaned using Vulpex Liquid soap, which successfully removed the gilder’s wax and unoriginal bronze paint on the water-gilded surface. The painting was then reframed and the reverse was sealed with Melinex and aluminium tape to avoid any debris being trapped behind the stretcher bars in the future.

Portrait of Charles Lyell by Emily Merrick, 1884

Sophia Boosalis and Jack Chauncy retouching the Portrait of Charles Lyell / © Marie-Christine Livage

The treatment of the Portrait of Charles Lyell focused on the vulnerable areas of delaminating paint. The areas of raised brittle paint were consolidated with a 7% solution of Aquazol 50 in Iso-propanol using a heat gun and silicone brush to manipulate the degraded paint. A significant step in this treatment involved locally retouching the painting with a pigmented varnish using a 20% solution of Paraloid B72 with dry pigments and a 20% solution of Laropal A81 in Shellsol A and Shellsol D. The painting was then sprayed with a Regalrez varnish in order to achieve an even saturation and gloss.

Portrait of Narcissus Marsh, 1704

Cat Dussault consolidating flaking paint on the Portrait of Narcissus Marsh / © Marie-Christine Livage

Due to its considerable size, the Portrait of Narcissus Marsh was conserved on the dining hall balcony. As a collective, five students cleaned the surface of the painting with saliva and cotton swabs. Furthermore, areas of flaking paint were carefully consolidated using isinglass. The adhesive was carefully fed into the cracks using a brush and then gently flattened with a hot spatula.

Team members from Gander & White re-hanging the Portrait of John Conant in the dining hall / © Alexandra Earl

Georgie Dennis (organiser and freelance conservator) and Alexandra Earl observing the re-hanging of the portraits in the dining hall / © Marie- Christine Livage

Following the completion of each conservation treatment, the paintings were carefully re-hung on the dining hall walls by an expert team from Gander & White. It was rewarding to appreciate fully each artworks’ improved appearance and identify painterly details which had previously been obscured by dust and yellowed varnish.

Overall, the Summer School was an incredible experience and it was an absolute pleasure for everyone to have the opportunity to restore these portraits in a stunning environment. It was fascinating to observe and discuss the various approaches to each treatment, as well as learn from each other’s experiences and skills. Ultimately, it was a brilliant opportunity to work with a diverse group of enthusiastic and diligent conservators who share the same passion for preserving paintings.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements go to Georgie Dennis and Marie-Christine Livage for not only organising the Summer School but for their invaluable guidance and encouragement during each treatment. Gratitude goes to Gander & White for ensuring the safe de-instalment and re-hanging of the paintings.

Furthermore, thanks go to Tru-Vue for sponsoring the formal dinner on the last day in Oxford. The evening granted a lovely opportunity to reflect and celebrate our achievements among the newly restored paintings in the dining hall.

Finally, the Summer School conservators wish to thank all the staff at Exeter College for their immense generosity in permitting access to their paintings and for welcoming us on site at this beautiful college.