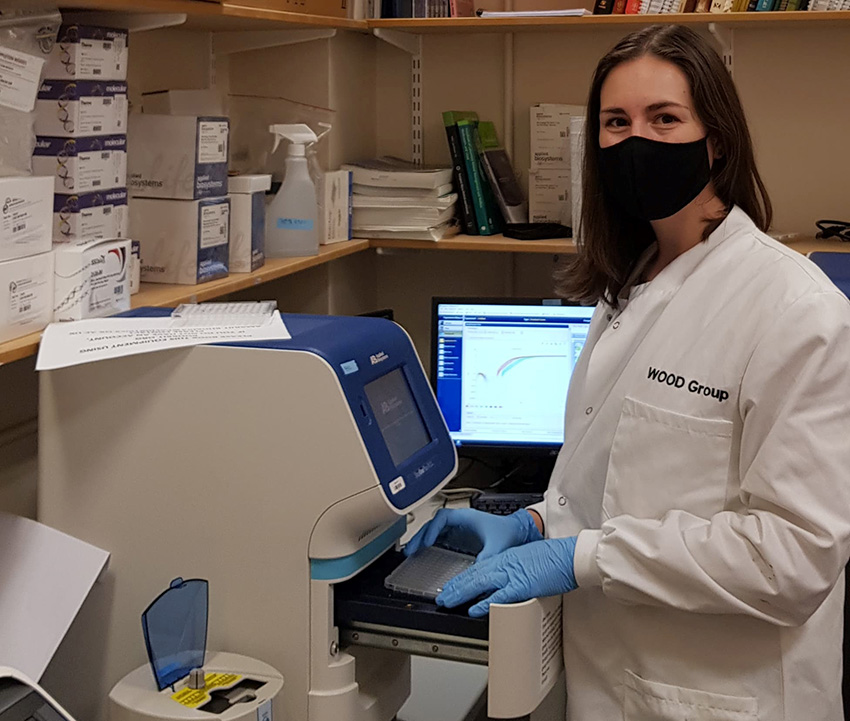

Graduate research: Britt Hanson on gene editing

To mark Women’s History Month Exeter College news intern Costi Levy has been speaking to Exeter students and alumnae about their work. In this instalment Britt Hanson (2017, DPhil in Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics) tells Costi about the challenges she may face as a woman at a critical point in her career.

‘Since I heard about CRISPR, the Nobel Prize winners Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna were my role models. They were forging such an important scientific path and sticking to their morals and integrity the whole time.’

CRISPR gene editing, ‘which is basically molecular scissors’, is at the centre of Britt’s research. Her work focuses on the application of the technology for therapeutic development of fatal and highly debilitating hereditary neuromuscular diseases, namely Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Spinal Muscular Atrophy. She notes that current treatments for the diseases are highly invasive and require repetition, whereas a CRISPR based treatment would permanently correct the causative genetic defects.

Britt was drawn to gene editing during her undergraduate degree at the University of Cape Town and masters at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. ‘What led me to Oxford was working on my masters project with my supervisor in South Africa,’ Britt notes. ‘He had a connection with my current supervisor in the lab here in Oxford and he said, “dream big, go overseas, do something amazing and apply to Oxford”’. Britt had never been to Oxford before she applied and describes the experience as ‘quite daunting but incredibly exciting’.

Aged 27, Britt is aware of challenges that she may face: ‘there will be lots of hurdles which will shape whether I can be as successful as I want to be’. She explains what can at times feel like a dichotomy between developing her career and suspending it to start a family. This question is particularly pertinent to her, she emphasises, as a woman studying her DPhil in her late twenties/early thirties. ‘This is really when you want to push your career in science. The first few years of your post-doc are really important … but that is unfortunately the same time as when you are trying to decide on your personal life’.

Despite potential challenges, Britt is determined to set herself up as well as possible in her science career. She cites certain measures which could be taken to support women in this moment, for example devising a way to account for a career break in a scientist’s CV, and the normalisation of paternity leave – a project which is well under way and would positively impact both men and women. Moreover, she emphasises that finding a successful balance between family and career is possible. Strong female role-models can be found at all levels in gene editing, from Nobel Prize winners to post-docs in the lab who balance work and their personal life. Britt also highlights her mother, a pharmaceutical researcher, who took some time off work to have children, but worked hard and has enjoyed a very fulfilling career. ‘I look up to them,’ Britt notes, ‘I still feel like I can’t balance the gym, friends and work!’