Reflections from the Chaplain: Good Friday

During the COVID-19 crisis Exeter College is providing Chapel services and spiritual reflection online, led by the Reverend Andrew Allen.

In an effort to provide the Exeter College community with spiritual support, in my role as chaplain, during this unusual and challenging time of lockdown, I am posting regular reflections from my home in Germany. Here is my latest, accompanied by a recording from the College Choir. If you would like to receive more reflections by email please let me know by emailing me at andrew.allen@exeter.ox.ac.uk. Or you can read all of my recent reflections and listen to the accompanying pieces of music by clicking here.

Good Friday

Behold the wood of the cross,

whereupon was hung the Saviour of the world.

O come let us worship.

Today is Good Friday. The most solemn day for Christians: the day when God’s love for the world is shown through the death of Jesus Christ. The cross is central to Christianity, and this day has been commemorated for nearly two thousand years in different ways, and this year is no exception. The words ‘behold the wood of the cross’ are used in the usual liturgy for Good Friday, and are very ancient. They are used when a cross is brought into the church, and those present venerate it; that is to say they bring themselves, their fears, their mistakes, their regrets, as well as their hopes, their challenges, and lay them at the foot of the cross. Not for some miraculous solution, but to bring them before the mercy and love of God, mercy and love expressed through the crucifixion of Christ.

I’ve been ordained for 11 years, and this is the first time I have had to write a reflection for Good Friday – usually the liturgy speaks more eloquently than I ever could – but we are in different times. But even in these exceptional circumstances I’m not sure what to say, so today I offer you space to reflect, to think, to be still.

When you read the words ‘behold the wood of the cross’ what image comes to mind?

Perhaps it is like one of the earliest depictions of the cross – the + scratched on one of the catacombs in Rome or Sicily or Malta, with the A and O either side, symbolising the grave that we all share in the hope of the resurrection?

Or perhaps it is like the small ivory panel – only a few inches long – the earliest image of the cross in the UK, of Christ with large feet and outstretched hands just slightly higher than the figures on the ground beside him.

Wood is an expensive luxury in the Mediterranean, and crosses were used again and again, they were valuable objects, and indeed research into Roman methods of death have shown that the convict carried only the cross bar, and would have been attached to the upright stake once the place of death was reached. Yet this is far removed from the tall and slender crosses with Christ many feet above the crowd, reigning in glory, wearing the crown of thorns. This iconography can be dated after 1238 when Emperor Baldwin II of Constantinople gave the relic of the crown of thorns to King Louis IX of France, in exchange for the French protection against invaders, and so we see the crown of thorns beginning to appear.

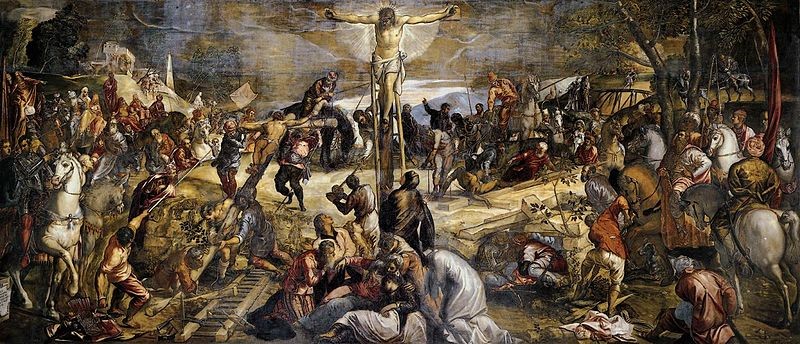

Or maybe when you think of the cross it is in a landscape full of people – of our Lady and the other women and the soldiers of course – the characters described in the gospel. But also other crowds – people from a different time and era, as in Tintoretto’s vast Crucifixion, which adores the council chamber of the Doges’ Palace in Venice.

Or maybe the cross you think of is one of reconciliation – like the simple and small cross of nails made from melted down metal from both the bombed out cathedrals of Dresden in Germany and Coventry in England.

Or perhaps you don’t think of any famous cross when you hear the words ‘Behold the wood of the cross.’ Maybe your cross is one you wear – made out of silver or gold – a present for a landmark in your life. Or maybe the cross means nothing to you because you come from another faith tradition, or sceptical or dismissive of the idea of religion. Whatever your image of the cross is, today, perhaps you might want to think what concerns and fears, which people and relationships, what hopes and aspirations are most important to you and spend some time thinking about these.

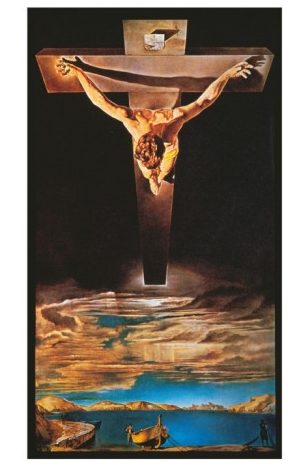

You might want to listen to Brahms’ requiem, which the current choir sang in concert in February 2020. This is the recording from the concert, held in St Martin in the Fields in London, and its accompanying notes are at the end of this article. And, as you listen, you might want to look at some of the below images of the crucifixion to help focus your thoughts. We’ve all had huge amounts to process, to rearrange, and re-imagine life, so perhaps we should see today as a gentle, quiet, and reflective day.

To listen to the College Choir singing Brahms’ requiem click here (the concert begins at about three minutes into the recording).

A full text of the Requiem is available here: http://www.classical-music.com/article/brahmss-german-requiem-text

Andrew Allen 10.iv.20

Ivory casket, c 420 AD. In the British Museum

Tintoretto, 1565, San Rocco, Venice

Cross of Nails, the cross of reconciliation, Coventry Cathedral

Dali, Christ of St John of the Cross, 1951, Glasgow Art Gallery

Programme Notes to Brahms: Ein deutsches Requiem

For many composers in the nineteenth century, a setting of the requiem, the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead, was a challenge to demonstrate sorrow, consolation, anger, eternal peace, and even fear of the Final Judgement all in one work. For some composers, the motivation was a commission for a patron, for others, it was even a reflection on their own impending death. Given Johannes Brahms’s recent relocation to Vienna, a traditional Latin-text setting of the requiem would have been more appealing to the Catholic audiences there. However, Brahms instead chose non-liturgical texts from Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible into German, an idea he may have got from his friend Robert Schumann, who reportedly had planned to compose such a work before his own death. Perhaps Ein deutsches Requiem was inspired by Schumann’s passing, or it was in memory of Brahms’s mother, for whose death he was not able to be present. Whatever the true motivation, the Brahms Requiem differs from all other requiems, as it was written less to honour the dead, and more to console those left behind.

The entire work consists of seven movements, each of which includes elements of the traditional Latin requiem: the first movement consolation, the second anger, the third joy for the dead as they find everlasting life, and so on. More an art song than an oratorio or opera, the work is entirely text-driven, although because the prospect of death means something different to everyone, there is great room for interpretation among performers. However, some movements are clearer than others; the extraordinary death culture of Vienna in the nineteenth century, with its grand funeral processions that would literally go on for miles, may have inspired at least the second movement. The fifth movement, the last to be composed, is a heart-wrenching scene in which the soprano’s character is on her deathbed, and the chorus serves as the choir of angels welcoming her to paradise. In contrast to these particularly Romantic parts of the work, the third and sixths movements end quite classically, with fugues reminiscent of Bach (whose works Brahms studied and championed), but with a nineteenth-century flair in rhythm and harmony.

Following the several premieres of the Requiem (one of which went poorly due to lack of preparation, exacerbated by the timpanist misunderstanding the fortepiano markings in his part — fp — and instead playing fortissimo), Brahms’s career skyrocketed, inspiring him to write two additional versions of the work. The first was a solo piano version, which he presented to Clara Schumann on Christmas 1866; the second in 1871 was for choir accompanied by piano duet, which became known as the ‘London Version’ because of its premiere at the London home of Sir Henry Thompson, a surgeon and polymath. The piano parts were played by his wife, Lady Kate Thompson, and Cipriani Potter, the then-retired principal of the Royal Academy of Music (whom Beethoven once asked for composition lessons). Four-hand piano music was popular throughout Europe and Britain during this period, as many symphonies were transcribed for amateur enjoyment at home, though the arranging was always done by an employee of the publisher. The London Version is therefore unusual, as Brahms himself (a virtuoso pianist) made the transcription. This chamber performance provides a closer look into a great masterpiece that, in its original version, required massive performing forces. It beckons musicians and audiences alike to reflect upon what death means to us today, nearly 150 years following the premiere of this tremendous, yet profound setting of a requiem that does not condemn the fundamental human nature of death, but invites us to see it in many different lights, and ultimately find a sense of peace.

Christopher Holman, Junior Organ Scholar.